Intro: The Ascent and the Awful Realization

I can still recall my very first trek at a high altitude like it was yesterday. In fact, it was not some grand K2 base camp expedition, but simply a beautiful and challenging three-day hike to a moderately high pass in the Himalayas. When I was 17, I felt like I was made of steel, and, as a young traveler usually does, I thought that if I could easily run a 5K, I could also manage the altitude.

But little did I know mountains don’t care, they only care about the one who listens to their body up close. Suddenly on my way up to the last day I started feeling dizzy and there was a blackout and I couldn’t get up.

What was wrong with me, of course, was Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), a stealthy, silent bandit of fun that targets unprepared hikers. I was not acquainted with the rules. I did not respect the mountain. Eventually, I had to go down a day earlier, feeling shameful, but, importantly, safe. That failure, that agonizing and maddening moment on the mountainside, was the lesson for me of the five indispensable life-saving rules that I follow now.

This guide is your ultimate, the stuff I wish someone had told me when I was 17.

What Exactly Is AMS, and Why Does It Feel So Awful?

Let’s be real for a second. The air up high isn’t just “thin” in a poetic sense; it literally has less oxygen pressure. When you ascend rapidly and by rapidly I mean going from sea level to around 10,000 feet in a couple of days your body simply cannot accommodate the change.

Imagine your body to be a high-performance engine, which is suddenly required to run on lower-octane fuel. To make up for the shortage, the engine makes the user breathe faster and more vigorously. However, there are instances wherein this is insufficient leading to a minor tantrum by the part of the user as brain and lungs fluid balance is shifting.

The 5 Non-Negotiable Rules for Your First High-Altitude Trek

Rule 1: Ascent Rate is King (Don't Be a Hero, Seriously)

This is the rule that I completely violated on my first trek, and I believe that it is the most difficult one for young travelers to acknowledge. So, the point is that one cannot and should not rush the process of acclimatization. Here, someone’s fitness level does not play any role. Even an Olympic athlete has to take it slow. Your body acclimates at its own pace which is determined by the physiology rather than the power of the will.

Yes, I am aware that it ruins your schedule. It also means that you have to stay for an additional day or two on the trail. But you have to believe me that spending that extra day in a tea-serving, lower altitude lodge is a million times better than having to be airlifted due to HACE. A sagacious guide once said to me, “Walk high, sleep low.” This suggests that you can hike a bit more during the day for your body to get used to the altitude, but you have to be at the lower, safer altitude for sleeping. I think that this mental trick works great: you get the feeling that you have progressed even if you haven’t changed your sleeping place.

Rule 2: Hydrate or Fail (Water, Water, Everywhere)

This might seem obvious, but it is the single most overlooked factor and the easiest to control. At high altitude, water losses are significantly greater than at sea level. The reason is that the body tries to provide more oxygen for the lungs by increasing ventilation (thus water is lost through breathing, usually involuntarily) and the air is generally dry and cold.

If you are not urinating frequently, and I mean really frequently, then you are not taking in sufficient amounts of fluid. I think that people are hesitant because they do not want to use the unpleasant toilets on the trail, but to be honest, this is only a minor inconvenience in comparison to the awful headache that stops your whole trip.

- The Magic Number: A person should consume a minimum of 3–4 liters of water daily and, on top of that, take some more during the hike.

- Boost It Up: Have hydration tablets or electrolyte powders with you. They are revolutionizers. They make it easier for the body to absorb and retain water, turning it into a much more efficient way of combating the dehydrating effects of altitude. Your urine really is your gauge up here.

Rule 3: Carb Load Like You Mean It (Fueling the Machine)

So here we are at slow ascent and hydration. What about food? At a high altitude, the body uses energy in a different way and, frankly, it is less efficient.

Oxygen is limited in the body; thus, the latter prefers to burn carbohydrates for energy. This is because carbs need less oxygen than fats or proteins for their metabolism. It is like your engine is asking for high-octane fuel (carbs) to function properly when the air pressure is low. If you were to follow a high-protein, low-carb diet at that height, you will be making the mechanisms that help your body the most life-threatening ones.

I see so many trekkers trying that protein bars and nuts are good enough for them to snack on, without knowing that they are actually harming themselves. What they lack is the essential energy that is readily available.

- Embrace the Starch: Think rice, pasta, potatoes, porridge, and bread. Seriously. If you are going to trek somewhere like Nepal, this will give you the insight why rice and lentil curry (Dal Bhat) is the perfect fuel. Do it. Do it in large quantities.

- Keep Snacking: Your appetite might disappear at altitude, which is a common AMS symptom. However, you need to force yourself to eat. Keep very digestible snacks close at hand: hard candies, dried fruit, granola bars, and chocolate. The sugar is there to fulfill that very fast chain of oxygen-poor energy. I think the main point here is not seeing it as food but as fuel.

“Key Takeaway: At altitude, the body calls for fast carbs. Pay attention to it. Go starch, and don’t stop the energy even if you are not feeling hungry”

Rule 4: Know When to Tap Out (Immediate Descent is the Only Cure)

This rule is the one that differentiates the intelligent trekker from the reckless one. Besides, it is the one that requires the most self-knowledge and humility.

One of the phrases you’ve probably heard is, “tough it out.” High altitude, however, is the place where “toughing it out” might cost you your life. The biggest error I usually see made by young, fit travellers is that they confuse mild symptoms of AMS with pure tiredness. Because of this, they ignore the headache or the slight nausea as they are being pushed by their group or the itinerary, which is just their ego speaking.

If you experience moderate to severe symptoms such as unrelenting headache, vomiting repeated, or, definitely not, confusion, difficulty walking in a straight line (ataxia), or severe shortness of breath, then you are required to go down immediately.

Rule 5: Understand the Power of Prophylaxis (Medication is a Tool, Not a Crutch)

About medication, everyone has their own different view; however, as a content strategist whose priority is safety, I would advise you to see your doctor. There is no skipping pre-trip planning.

The best and only drug on the market for the prevention and treatment of AMS is a prescription medicine called Acetazolamide (Diamox).

- When to Use It: The general practice is that Diamox is taken 24 hours before the ascent, continued for the first few days at high altitude, or as long as the ascent is going on.

- The caveat: Diamox is not a magic barrier. Some side effects (tingling sensations in fingers and toes, frequent urination—surprise!) may occur. Most importantly, it cannot substitute for slow ascent. It is a helper, a tool, not a violator of Rule #1. In case you are taking it, you should also let your guide know.

Consult your doctor about getting a Diamox prescription and the appropriate dosage and timing for your itinerary. It is a source of comfort even if you decide not to take it.

Conclusion: Respect the Mountain, Respect Yourself

I agree that this has been a lot of information and maybe some parts of it are a little bit scary. However, I think understanding the risk is the first step in solving it, so it’s okay.

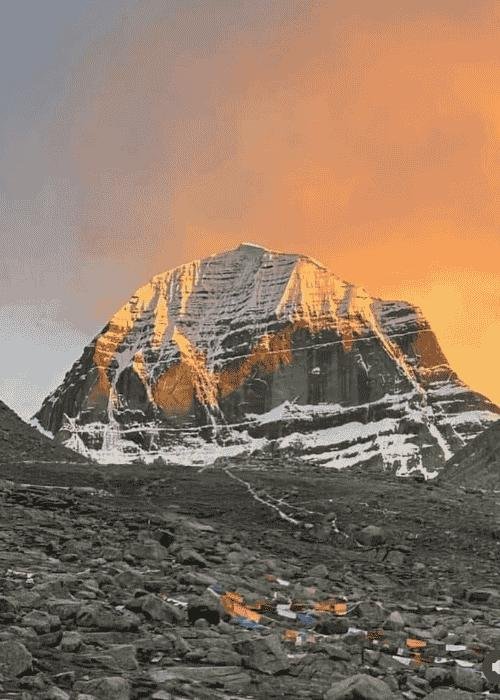

I wish the energetic, ambitious traveler in his/her 20s to go through the most incredible, life-changing experience possible. High-altitude trekking is amazing. It takes away everything to the basics, offers the most stunning views, and gives you an unbeatable feeling of achievement.

But, your primary task is to return safely.

If you are under pressure to continue at the same pace, or the climb gets difficult and you are thinking of skipping that rest day, think of those five non-negotiable rules. They are the key to exchanging an AMS headache with a lifetime of fantastic memories.

- Ascend slowly.

- Hydrate constantly.

- Carb up heavily.

- Descend immediately if symptoms worsen.

- Use Diamox wisely.

The mountain is going to be there forever. You can always take your time, enjoy the air (which is thin, by the way) responsibly and you will be able to make memories that will last forever – without the side of vomiting, I hope!

Good luck and happy trails.